IntroductionEinleitung

Further complicating factors for the study and analysis of ancient Central American writings are the missing or distorted historical traditions, as well as the current political and climatic situation of the areas where written testimonies can be found. Diego de Landa, a missionary responsible for the genocide and book burnings, is one of the sources:

Weitere erschwerende Faktoren für das Studium und die Analyse alter zentralamerikanischer Schriften sind die fehlenden oder verfälschten historischen Überlieferungen sowie die aktuelle politische und klimatische Situation in den Gebieten, in denen schriftliche Zeugnisse zu finden sind. Diego de Landa, ein für den Völkermord und die Bücherverbrennungen verantwortlicher Missionar, ist eine der Quellen:

Diego de Landa

Relación de las cosas de Yucatán

Hallámosles gran número de libros de estas sus letras, y porque no tenían cosa en que no hubiese superstición y falsedades del demonio, se los quemamos todos, lo cual sentían a maravilla y les daba pena.

We found among them a great number of books with these letters, and because they contained nothing free from superstition and the wiles of the devil, we burned them all, what the Indians deeply regretted and lamented.Wir fanden bei ihnen eine große Zahl von Büchern mit diesen Buchstaben, und weil sie nichts enthielten, was von Aberglauben und den Täuschungen des Teufels frei wäre, verbrannten wir sie alle, was die Indios zutiefst bedauerten und beklagten.

The decipherment of the Maya script already began with the questionable attempts of the conquistadors; de Landa proclaimed an alleged Maya Alphabet

, which he recorded for posterity. Possibly he failed due to the lack of cooperation of his informants, but certainly due to his own linguistic incomprehension; in any case, he was unable to adequately describe the Maya writing system. Nevertheless, his records are one of the most important sources for research.

The four surviving codices contain calendar records and astronomical calculations. With these, scientists in the 19th century succeeded in reconstructing the Maya numerical and calendar system. Special mention should be made of the librarian Ernst Wilhelm Förstemann, who was able to decipher the 20-number system and calendar counts using the Dresden Codex.

The British anthropologist Sir John Eric Sidney Thompson was one of the leading Maya researchers of the 20th century and essentially worked out the correlation between the Maya calendar and the Gregorian calendar valid today. For Thomson, the Mayan characters were logographic symbols; he and the American and Western European researchers under his influence were unable to decipher and explain the writing system.

In 1952, Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov from Leningrad, today’s Saint Petersburg, presented the result of his many years of work. Knorosov knew the pamphlets of bishop Diego de Landa and possessed a copy of the Dresden Codex. From the analyses of the character frequency and comparisons of the documents accessible to him, Knorozov concluded that the Maya script was a logosyllabic script, i.e. a syllabic script with additional logographic elements. Despite the convincing evidence and the confirmation of the ancient Americanist Tatiana Avenirovna Proskouriakoff, who lived in the USA and who, unlike Knorozov, had the opportunity to visit the Maya sites in Mexico and Guatemala, many Western researchers initially rejected the interpretation of the glyphs as a syllabic script, in Thomson’s words as Soviet propaganda

.

In the meantime, the Maya script has been almost completely deciphered based on the analyses of Knorosov and Proskouriakoff, both received an award for their services to deciphering the Maya script, and the next generation has the opportunity to revive the history of this sunken culture.

There is already a range in Unicode (15500 - 159FF) set aside for Mayan script. However, the graphic adaptation of the characters requires a complex system of additional control symbols whose functionality has not yet been worked out. Therefore, there is no generally valid proposal for the allocation of the characters, nor is there a functioning input system [as of April 2024]. For demonstration purposes I have created my own system using an additional unicode area in the PUA range.

Die Entzifferung der Mayaschrift begann bereits mit den fragwürdigen Versuchen der Eroberer; de Landa proklamierte ein angebliches Maya-Alphabet

, das er für die Nachwelt festhielt. Möglicherweise scheiterte er an der mangelnden Zusammenarbeit seiner Informanten, mit Sicherheit aber an seinem eigenen linguistischen Unverständnis, jedenfalls war er nicht in der Lage, das Schriftsystem der Maya adäquat zu beschreiben. Trotzdem stellen seine Aufzeichnungen eine der wichtigsten Quellen für die Forschung dar.

Die vier erhaltenen Codices enthalten Kalenderaufzeichnungen und astronomische Berechnungen. Damit gelang es Wissenschaftlern im 19. Jahrhundert, das Zahlen- und Kalendersystem der Maya zu rekonstruieren, dabei ist insbesondere der Bibliothekar Ernst Wilhelm Förstemann hervorzuheben, der anhand des Dresdner Kodex das 20er-Zahlensystem und die Kalenderzählungen entschlüsseln konnte.

Der britische Anthropologe Sir John Eric Sidney Thompson war einer der führenden Mayaforscher des 20. Jahrhunderts und erarbeitete im Wesentlichen die Korrelation zwischen dem Mayakalender und dem heute gültigen gregorianischen Kalender. Die Schriftzeichen der Maya waren für Thomson logographische Symbole, eine Entzifferung und Erklärung des Schriftsystems gelang ihm und den unter seinem Einfluss stehenden amerikanischen und westeuropäischen Forschern damit nicht.

1952 präsentierte Juri Walentinowitsch Knorosow aus Leningrad, dem heutigen Sankt Petersburg, das Ergebnis seiner langjährigen Arbeit. Knorosow kannte die Pamphlete des Bischofs Diego de Landa und besaß eine Abschrift des Dresdner Kodex. Aus den Analysen der Zeichenhäufigkeit und Vergleichen der ihm zugänglichen Dokumente schloss Knorosow, dass die Mayaschrift eine logosyllabische Schrift sei, also eine Silbenschrift mit zusätzlichen logografischen Elementen. Trotz der überzeugenden Belege und der Bestätigung der in den USA lebenden Altamerikanistin Tatiana Avenirovna Proskouriakoff, die im Gegensatz zu Knorosow die Möglichkeit hatte, die Maya-Stätten in Mexiko und Guatemala zu besuchen, lehnten viele westliche Forscher die Interpretation der Zeichen als Silbenschrift zunächst ab, mit Thomsons Worten als sowjetische Propaganda

.

Inzwischen ist die Mayaschrift aufgrund der Analysen von Knorosow und Proskouriakoff fast komplett entziffert, beide erhielten eine Auszeichnung für Ihre Verdienste um die Entzifferung der Mayaschrift, und die Nachfolgegeneration hat die Möglichkeit, die Geschichte dieser versunkenen Kultur wiederzubeleben.

Es gibt bereits einen Bereich im Unicode (15500 - 159FF), der für die Mayaschrift vorgesehen ist. Allerdings erfordert die grafische Anpassung der Zeichen ein komplexes System an zusätzlichen Steuerungs-Symbolen, dessen Funktionalität noch nicht ausgearbeitet ist. Daher existiert auch noch kein allgemein gültiger Vorschlag für die Allokation der Zeichen, und auch kein funktionierendes Eingabesystem [Stand April 2024].

ProfileProfil

writing categorySchrifttyp

Maya belongs to the Mesoamerican script family. It is a logosyllabic script written in falling double columns from left to right.

Maya gehört zur mesoamerikanischen Schriftfamilie. Es ist eine logosyllabische Schrift, die in fallenden Doppelspalten von links nach rechts geschrieben wird.

periodZeitraum

250 BCE – 900 CE250 BCE – 900 CE

languagesSprachen

- Maya

unicodeUnicode

Maya 15500 – 15AFF

Maya Numerals 1D2E0 - 1D2FF

Maya Numbers and Dates E200 – E2FF

Maya Basic Syllables E300 – E3FF

There is a reserved area for Maya script in Unicode, but no allocation of the individual characters, with the exception of the numbers. I have allocated some of the syllables in a sensible order. The font I have created for this page adds the E2 and E3 blocks of the Private Use Area to display the calendar. Es gibt im Unicode einen reservierten Bereich für Mayaschrift, allerdings bisher keine Allokation der einzelnen Zeichen. Ich habe einige Silben in einer sinnvollen Reihenfolge zugeordnet. Der von mir für diese Seite kreierte Font verwendet zusätzlich die Blöcke E2 und E3 der Private Use Area für die Darstellung des Kalenders.

Family Tree America PazificStammbaum Amerika Pazifik

CharactersSchriftzeichen

syllablesSilben

Maya script is a logosyllabic

writing system, i.e. a script that combines characters for syllables and symbols for meaning. Like in Japanese, terms can be represented in different ways, purely as syllables, as logograms, or as a combination of both. In Maya script, the individual elements of a glyph are arranged in a rounded square, and they are graphically adapted for this purpose.

Die Schrift der Maya ist eine logosyllabische

Schrift, das heißt, eine Schrift, die Zeichen für Silben und Bedeutungssymbole kombiniert. Etwa wie im Japanischen können Begriffe unterschiedlich dargestellt werden, rein aus Silben zusammengesetzt, als Bedeutungszeichen (Logogramm), oder als Kombination aus beidem. In der Mayaschrift werden die einzelnen Elemente eines Begriffs in einem abgerundeten Quadrat angeordnet und dafür entsprechend grafisch angepasst.

Primary glyphsPrimärzeichen

aaeeiioouub’aɓab’eɓeb’iɓib’oɓob’uɓupapapepepipipopopuputatatetetititototutut’otʼot’utʼukakakekekikikokokukuk’akʼak’ekʼek’ikʼik’okʼok’ukʼulalalelelililololulumamamememimimomomumunananenenininononunuyajayejeyijiyojoyujuwawawiwiwowohahahehehihihohohuhujaxajexejixijoxojuxusasasisisusuxaʃaxiʃixoʃoxuʃutzaʦatziʦitzuʦutz’aʦʼatz’iʦʼitz’oʦʼotz’uʦʼuchatʃachetʃechitʃichotʃochutʃuch’atʃʼach’otʃʼoIn addition to these main syllabic glyphs, there are further secondary glyphs for each syllable, which are used for multi-syllabic words. The secondary characters are reduced to core elements of each syllable, and have either a narrower width or height, depending on where they are attached to the main character. In this way, each word can be composed of syllables.

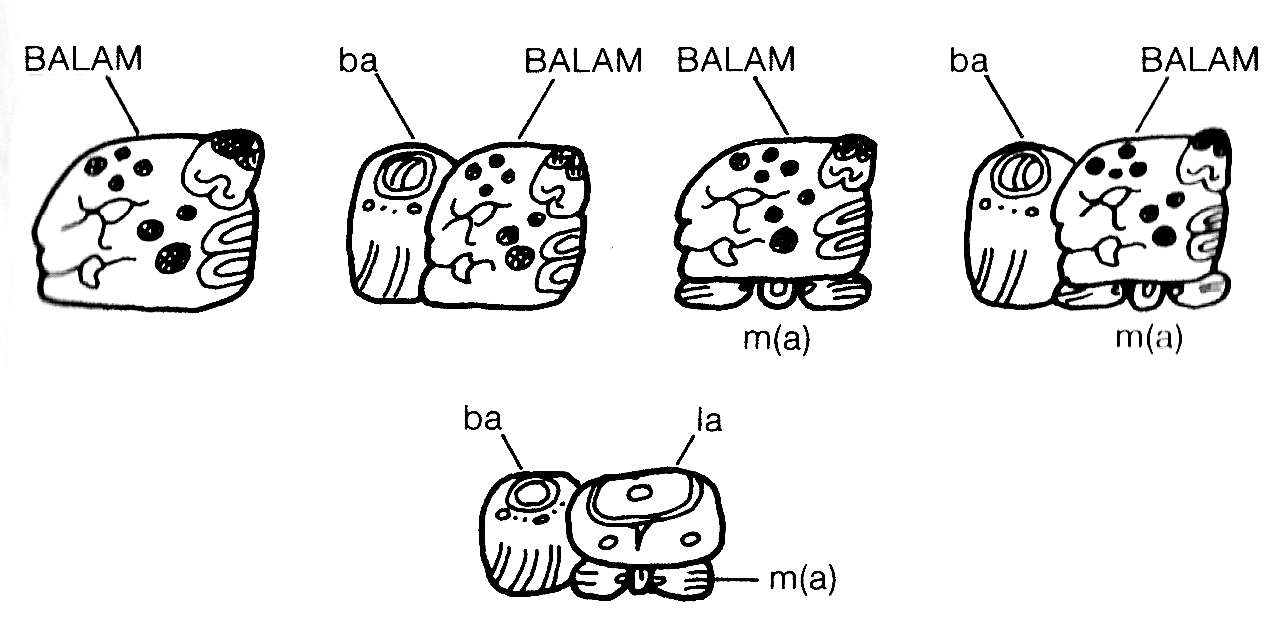

Another group of glyphs are the logograms for concrete things or names, which can complement or replace the syllabic word glyphs. The word Balam

(jaguar) can thus be written in several different ways:

Zusätzlich zu diesen Hauptsilbenzeichen gibt es für jede Silbe weitere sekundäre Zeichen, die bei mehrsilbigen Wörtern verwendet werden. Die Sekundärzeichen sind reduziert auf die grafischen Besonderheiten jeder Silbe und haben entweder eine schmalere Breite oder Höhe, je nachdem wo sie an das Hauptzeichen angefügt werden. So kann jedes Wort aus Silben zusammengesetzt werden.

Eine weitere Zeichengruppe sind die Logogramme für konkrete Dinge oder Namen, die die silbischen Wortzeichen ergänzen oder ersetzen können. Das Wort Balam

(Jaguar) lässt sich so auf mehrere verschiedene Arten schreiben:

For BALAM there is a logogram in the form of a jaguar’s head; this can stand alone for the term jaguar

(logograms are transcribed with capital letters in Latin). However, it is also possible to use the logogram as a primary character and add syllable components such as ba and ma as secondary elements. Finally, it is also possible to compose the whole word of syllables without the logogram: ba-la-m(a)

; in this case, the middle syllable la is written as the primary character, the others are grouped around it. The final coda is not pronounced unless it is a pure vowel syllable. In the syllable ma, one can see the relationship of the secondary sign to the primary sign; it is the bow written above the letter in the primary sign.

Furthermore, there are determinatives for grammatical purposes, with which words and sentences can be completed.

Für BALAM gibt es ein Logogramm in Form eines Jaguarkopfes; dieses kann alleine für den Begriff Jaguar

stehen (Logogramme werden in der lateinischen Umschrift mit Großbuchstaben gekennzeichnet). Es ist aber auch möglich, das Logogramm als Primärzeichen zu verwenden und Silbenbestandteile wie ba und ma als Sekundärelemente hinzuzufügen. Schließlich ist es auch möglich, das ganze Wort aus Silben zusammenzusetzen, ohne das Logogramm: ba-la-m(a)

; dabei wird die mittlere Silbe la als Primärzeichen geschrieben, die anderen um das Zeichen herum gruppiert. Der letzte Silbenauslaut wird nicht gesprochen, es sei denn, es ist eine reine Vokalsilbe. Bei der Silbe ma erkennt man die Verwandtschaft des Sekundärzeichens zum Primärzeichen, es ist die Schleife, die im Primärzeichen über dem Buchstaben geschrieben wird.

Weiterhin gibt es Bestimmungszeichen für grammatische Zwecke, mit denen Worte und Sätze ergänzt werden können.

NumbersZahlen

The Mayan number system is a place value system based on 20 and contains the digit zero. The calendar based on it consists of several periods (counts

) and precisely represents months, years and Venus orbits; in the long run the calendar is more accurate than the Gregorian calendar used today. By synchronising it with our present-day calendar, the history of the Mesoamerican peoples could be placed in time.

Numbers, weekdays and months also have their own glyphs.

Das Zahlensystem der Maya ist ein Stellenwertsystem auf der Basis 20 und enthält die Ziffer Null. Der darauf basierende Kalender besteht aus mehreren Perioden (Zählungen

) und bildet präzise Monate, Jahre und Venusumläufe ab; damit ist der Kalender genauer als der heute benutzte gregorianische Kalender. Durch die Synchronisation mit unserem heutigen Kalender konnte die Geschichte der mesoamerikanischen Völker zeitlich eingeordnet werden.

Auch die Zahlen, Nummern, Wochentage und Monate haben eigene Zeichen.

NumbersZahlen

012345678910111213141516171819Head numbers (ordinal numbers)Kopfzahlen (Ordinalzahlen)

0.1.2.3.4.5.6.7.8.9.10.11.12.13.14.15.16.17.18.19.The Maya calendarDer Mayakalender

The Maya calendar consists of several partial calendars. A complete date begins with an initial series

, composed of an introductory glyph and the long count of the days that have passed since the zero date. The last digit of the long count stands for the number of days (in a 20-days-unit). This is followed by the supplementary series

, which consists of the ritual Tzolk’in, further day cycles, a detailed moon calendar, and the Haab’.

Der Kalender der Maya besteht aus mehreren Teilkalendern. Ein vollständiges Datum beginnt mit einer Initialserie

, bestehend aus einer Einführungsglyphe und derLangen Zählung der seit dem Nulldatum verflossenen Tage. Die Lange Zählung wird mit der Tagesangabe abgeschlossen. Es folgt die Ergänzungsserie

, die aus dem rituellen Tzolk’in, weiteren Tageszyklen, einem detaillierten Mondkalender, sowie dem Haab’ besteht.

The Long CountDie lange Zählung

The Long Count was used for historical and astronomical records. It corresponds to our Julian Day Number. It is a counting of the days since the beginning of the count on the 13th of August 3114 BCE (according to the Gregorian calendar) in a (slightly modified) vigesimal numeral system: 20 K’in (days) make a Winal, 18 Winal a Tun (with 360 days thus about one year). 20 Tun are a K’atun, 400 Tun a B’aktun. From 20 B’aktuns (about 7890 years) on, higher units, Pictun, Calabtun, Kinchiltun and Alautun are used for dates in the distant future.

Die lange Zählung wurde für geschichtliche und astronomische Aufzeichnungen verwendet. Es ist eine Zählung der Tage seit dem Anfang der Zählung am 13. August 3114 v.d.Z. (nach dem gregorianischen Kalender) im (modifizierten) Zwanzigersystem: 20 K’in (Tage) ergeben ein Winal, 18 Winal ein Tun (mit 360 Tagen damit etwa ein Jahr). 20 Tun sind ein K’atun, 400 Tun ein B’aktun. Ab 20 B’aktuns (etwa 7890 Jahren) werden höhere Einheiten, Pictun, Calabtun, Kinchiltun und Alautun für Daten in der fernen Zukunft verwendet.

date unitsDatumseinheiten

initial glyphInitialglypheKinchiltunCalab’tunPiktunB’aktunK’atunTunWinalKinKinchiltunCalab’tunPiktunB’aktunK’atunTunWinalKinThe origin of creation, or rather, according to the Popol Vuh, the beginning of the forth age, in which we are living, is the date 13.0.0.0.0, written out 13 B’aktun 0 K’atun 0 Tun 0 Winal 0 K’in, based to the latest research the 13th of August 3114 BCE. This zeroth B’aktun was called 13 instead of zero for religious reasons, the following B’aktun got the number 1. Thus the creation date 13.0.0.0.0 was repeated on 23 December 2012, we are now living in the 13th B’aktun again – however, after the completion of the current B’aktun, the 14th B’aktun will dawn and continue to be counted in the base-20 system. The number 13 stands for the thirteen main joints of the human body: three on each arm and leg, and the joint on the neck.

The long count is introduced by an initialisation glyph

which usually displays the patron of the Haab’ month. This is usually followed by the indications for B’aktun, K’atun, Tun, Winal and K’in. The earliest date found so far is – apart from the zero date – 7 B’aktun 16 K’atun 3 Tun 2 Winal 13 K’in (the 7th of December 36 BCE). The latest documented date is on a stele in Cobá and includes place values up to Alautun (about 63 million years in the future). As the heyday of the Maya lasted from around the third to the ninth century, most of the dates are from the 8th or 9th B’aktun.

Der Ursprung der Schöpfung, oder besser nach dem Popol Vuh der Beginn des vierten Zeitalters, in dem wir leben, ist das Datum 13.0.0.0.0, ausgeschrieben 13 B’aktun 0 K’atun 0 Tun 0 Winal 0 K’in, nach neuesten Forschungen der 13. August 3114 v.d.Z. Dieses nullte B’aktun wurde aus religiösen Gründen 13 statt 0 genannt, das folgende B’aktun bekam die Nummer 1. Damit wiederholte sich das Schöpfungsdatum 13.0.0.0.0 am 23. Dezember 2012, wir leben jetzt wieder im 13. B’aktun - allerdings wird nach Vollendung des aktuellen B’aktuns das 14. B’aktun anbrechen und im Zwanzigersystem weitergezählt. Die Zahl 13 steht für die dreizehn Hauptgelenke des Menschen: drei an jedem Arm und Bein, sowie das Gelenk am Hals.

Die lange Zählung wird eingeleitet durch eine Initialisierungsglyphe, die normalerweise den Patron des Haab’-Monats zeigt. Danach folgen die Angaben für B’aktun, K’atun, Tun, Winal und K’in. Das früheste Datum, das bisher gefunden wurde, ist – abgesehen vom Nulldatum – 7 B’aktun 16 K’atun 3 Tun 2 Winal 13 K’in (der 7. Dezember 36 v.d.Z.). Das späteste belegte Datum befindet sich auf eine Stele in Cobá und umfasst Stellenwerte bis Alautun (etwa 63 Millionen Jahre in der Zukunft). Da die Blütezeit der Mayas etwa vom dritten bis zum neunten Jahrhundert währte, sind die meisten Datumsangaben aus dem 8ten oder 9ten B’aktun

TheDer Tzolk’in

Usually, when a date is given, the long count is followed by the count of days

, the Tzolk’in. The Tzolk’in date is a permutation of the numbers 1 to 13 (referring to the 13 main joints of the body) and the twenty patron deities for the days. Both are incremented with each day, so that after 260 days the same Tzolk’in date is reached again.

Üblicherweise folgt bei einer Datumsangabe der langen Zählung die Zählung der Tage

, der Tzolk’in. Das Tzolk’in-Datum ist eine Permutation aus den Zahlen 1 bis 13 und den zwanzig Schutzgottheiten für die Tage. Beides wird mit jedem Tag hochgezählt, sodass nach 260 Tagen wieder das gleiche Tzolk’in-Datum erreicht ist.

daysTage

ImixIk’Ak’b’alK’anChikchanKimiManik’LamatMulukOkChuwenEb’B’enIxMenKib’Kab’anEtz’nab’KawakAjawThe Tzolk’in is still used as a ritual calendar. In its 260-day cycle, astronomical as well as mythological factors are linked to everyday circumstances. The duration corresponds to the original agricultural period of maize from slash-and-burn to harvest, it roughly corresponds to the duration of human pregnancy, as well as quite exactly one third of a synodic Mars year (the duration until the planet is at the same position as seen from Earth). In the city of Izapa, which is believed to be the origin of the calendar, the duration between two zenith positions of the sun is exactly 260 days.

The Tzolk’in is counted since the origin beginning with the date 4 Ajaw. This date refers to the first four humans, the lords (Ajaw) of creation, who were created in the fourth age (the one we live in) from corn by the gods. The first day of each 13th Winal, Tun, K’atun or B’aktun falls on the day 4 Ajaw.

Der Tzolk’in wird als ritueller Kalender nach wie vor verwendet. In seinem 260-Tages-Zyklus sind astronomische sowie mythologische Faktoren mit alltäglichen Gegebenheiten verknüpft. Die Dauer entspricht der ursprünglichen Agrarperiode des Maises von der Brandrodung bis zur Ernte, sie entspricht in etwa der Dauer der menschlichen Schwangerschaft, sowie recht genau einem Drittel eines synodischen Marsjahres (die Dauer, bis der Planet von der Erde aus gesehen an der gleichen Position steht). In der Stadt Izapa, die als Ursprung des Kalenders vermutet wird, beträgt die Dauer zwischen zwei Zenitständen der Sonne exakt 260 Tage.

Gezählt wird der Tzolk’in seit dem Ursprung beginnend mit dem Datum 4 Ajaw. Dieses Datum bezieht sich auf die ersten vier Menschen, die Herren (Ajaw) der Schöpfung, die von den Göttern im vierten Zeitalter (in dem wir leben) aus Mais geschaffen wurden. Der erste Tag jedes 13. Winal, Tun, K’atun oder B’aktun fällt jeweils auf den Tag 4 Ajaw.

Further day countsWeitere Tageszählungen

The date was partly supplemented with other glyphs between Tzolk’in and Haab’. These characters were labelled backwards with the letters G to A by the Mayan researcher Sylvanus Morley, as he assumed that they represented a lunar calendar that was similar in structure to the long count. Additional glyphs, which were found later, kept the reverse order of labelling and were called Z, Y and X.

Die Datumsangabe wurde teilweise mit weiteren Glyphen zwischen Tzolk’in und Haab’ ergänzt. Diese Zeichen wurden von dem Maya-Forscher Morley rückwärts mit den Buchstaben G bis A bezeichnet, da er darin einen Mondkalender vermutete, der im Aufbau der langen Zählung glich. Weitere Glyphen, die später gefunden wurden, behielten die umgekehrte Reihenfolge der Beschriftung bei und wurden als Z, Y und X bezeichnet.

G1G2G3G4G5G6G7G8G9FZYSimilar to our days of the week, there were nine glyphs which change daily. Today, the are called Lords of the Night, and, since the names of these lords or guardians are not known, they are designated G1 to G9. Some of the glyphs have fixed coefficients, but these are not related to the order of the glyphs. Together with the following series of the lunar calendar, the numbers may help to calculate solar and lunar eclipses. Sometimes, the glyph is followed by the determinative glyph F, which probably can be translated as ... this is the lord of the night

. The count of the Lords of the Night starts with the glyph G9 on the zero date of the fourth age.

In Yaxchilán on the Usumacinta, almost all dates have an additional day count, which is missing at other sites. The glyphs labelled Z and Y are a 7-day count, whereby the glyph Z is optional and thus possibly a determinative glyph. However, the Z glyph carries the coefficient if both glyphs are written, otherwise the coefficient is part of the Y glyph. The zero date of the fourth age has the number 3, which may be an indication that this count and others start in a previous age.

The 7-day count together with the count of the Lords of the Night and the 13-day count of the Tzolkin results in a cycle of 819 days, which is sometimes confirmed by additional glyphs. The synodic orbital periods of all five planets known to the Mayans can be calculated from the 819-day cycle.

Ähnlich wie bei unseren Wochentagen gab es neun Glyphen, die täglich wechselten. Heute werden sie als Herren der Nacht bezeichnet, und da die Namen dieser Herren oder Wächter nicht bekannt sind, werden sie als G1 bis G9 bezeichnet. Einige der Glyphen tragen feste Koeffizienten, die aber nicht mit der Zählung zusammenhängen. Möglicherweise helfen die Zahlen zusammen mit der folgenden Mondkalenderserie bei der Berechnung von Sonnen- und Mondfinsternissen. Manchmal folgt auf die Glyphe die Bestimmungsglyphe F, die wahrscheinlich mit ... dies ist der Herr der Nacht

übersetzt werden kann. Die Zählung der Herren der Nacht beginnt mit der Glyphe G9 beim Nulldatum des vierten Zeitalters.

In Yaxchilán am Usumacinta haben fast alle Datumsangaben eine weitere Tageszählung, die an anderen Fundstellen fehlt. Die Glyphen, die mit Z und Y bezeichnet werden, sind eine 7-Tage-Zählung, wobei die Glyphe Z optional und damit möglicherweise eine Bestimmungsglyphe ist. Allerdings trägt die Z-Glyphe den Koeffizienten, wenn beide Glyphen geschrieben werden, ansonsten ist er Teil der Y-Glyphe. Der erste Tag des Nulldatums des vierten Zeitalters hat die Nummer 3, was vielleicht ein Hinweis darauf ist, dass diese Zählung und andere in einem früheren Zeitalter beginnen.

Die 7-Tage-Zählung zusammen mit der Zählung der Herren der Nacht und der 13-Tage-Zählung des Tzolkin ergibt einen Zyklus von 819 Tagen, der manchmal durch weitere Glyphen bestätigt wird. Aus dem 819-Tage-Zyklus können die synodischen Umlaufzeiten aller fünf den Mayas bekannten Planeten berechnet werden.

The Lunar SeriesDie Mondserie

The lunar series are based on an 18-month cycle. Each six-month period is dominated by one of three deities. The length of the months corresponds exactly to one lunation, i.e. the synodic orbital period of the moon. The length of the months is therefore (almost) alternately 29 or 30 days.

Die Mondserie basiert auf einem 18-monatigen Zyklus. Jede sechsmonatige Periode wird von einer von drei Gottheiten beherrscht. Die Länge der Monate entspricht genau einer Lunation, also der synodischen Umlaufzeit des Mondes. Die Länge der Monate ist also (fast) abwechselnd 29 oder 30 Tage.

EDC1C2C3BA29A30X1X1X2X2X2X3X4X4X4X5X5X5X6X6X7X7X8X9The lunar series start with the age of the moon represented by the glyphs E or D. They show the days after the sighting of the first crescent moon, which probably has to be confirmed by an authorized priest. Glyph E means twenty and is used only when the age of the moon is older than 19 days, carrying a coefficient 0 to 9. It is often followed by glyph D without coefficient. For a moon age less than 20, glyph D is written alone and carries the respective coefficient for the moon age.

A complete moon calendar cycle consists of 18 lunations (lunar months), which is 531 or 532 days. The first six months are ruled by the death god Hunhunahpú represented by the scull glyph C1. The second half year is ruled by a deity looking like the tonsured maize god or more likely like Ixquic, the princess of the underworld Xibalbá, represented by glyph C2. The last six months are ruled by the twin gods Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué, children of Hunhunahpú and Ixquic, often referred to as Jaguar God of Xibalbá; the glyph C3 shows a jaguar head with a protruding tooth. The twins Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué are the heroes of Mayan mythology and eventually became the sun and the moon when they died. The jaguar (balam) is an animal of the night, while the tooth is usually an attribute of the sun god. C3 is sometimes simplyfied and shows only the eye of the brothers (they had the same eyes). The C glyphes carry a coefficient from one to six, which determines the actual lunation of the half year for which the deity is responsible; for the first month a special prefix is used.

The C glyph is occasionally followed by a pair of glyphs called X and B. The latter is a determinative with the meaning ... this is the patron of the lunation

. There are nine X glyphs representing these patron deities, several of them existing in different and probably exchangeable variants. In my overview, I have assigned them to the 18 months, whereby interchangeable variants have been given the same name. The X glyphes correspond to the ruling gods and numbers of the lunations and do not carry any coefficients.

The last glyph of the lunar series, called glyph A, stands for the length of the actual lunation (which can be 29 or 30 days, mostly alternating to adapt the synodic period of the moon). The glyph itself stands for the number 20 (here I use another variant than for the moonage) and carries either the number nine or ten.

Die Mondreihe beginnt mit dem Alter des Mondes, das durch die Glyphen E oder D dargestellt wird. Sie zeigen die Tage nach der Sichtung der ersten Mondsichel, die möglicherweise von einem authorisierten Priester bestätigt werden musste. Die Glyphe E bedeutet zwanzig und wird nur verwendet, wenn das Alter des Mondes älter als 19 Tage ist. Sie trägt einen Koeffizienten von 0 bis 9. Ihr folgt häufig die Glyphe D ohne Koeffizient. Bei einem Mondalter von weniger als 20 wird die Glyphe D allein geschrieben und trägt den entsprechenden Koeffizienten für das Mondalter.

Ein vollständiger Mondkalenderzyklus besteht aus 18 Lunationen (Mondmonaten), also 531 oder 532 Tagen. Die ersten sechs Monate werden vom Todesgott Hunhunahpú beherrscht, der durch die Schädelglyphe C1 dargestellt wird. Das zweite Halbjahr wird von einer Gottheit regiert, die wie der Maisgott mit Tonsur oder eher wie Ixquic, die Prinzessin der Unterwelt Xibalbá, aussieht, repräsentiert von der Glyphe C2. Die letzten sechs Monate werden von den Zwillingsgöttern Hunahpú und Ixbalanqué, Kinder von Hunhunahpú und Ixquic, regiert, die oft als Jaguar-Gott von Xibalbá bezeichnet werden; die Glyphe C3 zeigt einen Jaguarkopf mit vorstehendem Zahn. Die Zwillinge Hunahpú und Ixbalanqué sind die Helden der Maya-Mythologie und wurden nach ihrem Tod zu Sonne und Mond. Der Jaguar (Balam) ist ein Tier der Nacht, während der Zahn üblicherweise ein Attribut des Sonnengottes ist. C3 wird manchmal vereinfacht dargestellt und zeigt nur das Auge der Brüder (sie hatten die gleichen Augen). Die C-Glyphen tragen einen Koeffizienten von 1 bis 6, der die tatsächliche Lunation des Halbjahres anzeigt, für das die Gottheit zuständig ist; für den ersten Monat wird ein besonderes Präfix verwendet.

Auf die C-Glyphe folgt gelegentlich ein Glyphenpaar namens X und B. Letzteres ist ein Determinativ mit der Bedeutung ... dies ist der Schutzpatron der Lunation

. Es gibt neun X-Glyphen, die diese Schutzgötter repräsentieren, wobei mehrere von ihnen in verschiedenen und wahrscheinlich austauschbaren Varianten existieren. In meiner Übersicht habe ich sie den 18 Monaten zugeordnet, wobei austauschbare Varianten den selben Namen erhalten haben. Die X-Glyphen entsprechen den herrschenden Göttern und Zahlen der Lunationen und tragen keine Koeffizienten.

Die letzte Glyphe der Mondreihe, genannt Glyphe A, steht für die Länge der eigentlichen Lunation (die 29 oder 30 Tage betragen kann, meist abwechselnd als Anpassung an die synodische Periode des Mondes). Die Glyphe selbst steht für die Zahl 20 (hier verwende ich eine andere Variante als für das Mondalter) und trägt entweder die Zahl neun oder zehn.

TheDer Haab’

As a supplement to the Tzolk’in, the Haab’ was used by the Maya to calculate sowing and harvesting times. This calendar is similar to our solar calendar today, it usually finalized the date series. The Haab’ divides the year into 18 Haab’ months with 20 days each, as well as a 19th short month with 5 unnamed days, which were considered unlucky days. From the dates that have been handed down, one can see that there were no leap days, so the calendar shifted slowly in relation to the solar year.

Als Ergänzung zum Tzolk’in diente der Haab’ den Maya zur Berechnung der Saat- und Erntezeiten. Dieser Kalender ähnelt unserem heutigen Sonnenkalender und schloss üblicherweise eine Datumsangabe ab. Der Haab’ unterteilt das Jahr in 18 Haab’-Monate mit je 20 Tagen, sowie einem 19. Kurzmonat mit 5 namenlosen Tagen, die als Unglückstage galten. An den überlieferten Daten kann man erkennen, dass es keine Schalttage gab, der Kalender sich also langsam gegenüber dem Sonnenjahr verschob.

Haab’ monthsHaab’-Monate

PopWo’SipSotz’SekXulYaxk’inMolCh’enYaxSak’KehMakK’ank’inMuwanPaxK’ayab’Kumk’uWayeb’In contrast to the ritual Tzolk’in, the day numbers 0 to 19 of a Haab’ month were counted up daily, after the 19th of a month followed the zeroth of the next month, after the 18th month followed the five unlucky days of the short month Wayeb’. The first day of creation fell on 8 Kumk’u, the eighth day of the month Kumk’u. The combination of 4 Ajaw with 8 Kumk’u is reached after 52 Haab’ years and is called the calendar round

. It corresponds to 73 Tzolk’in periods and exactly 130 synodic Venus orbits.

The Haab’ calendar was changed with the Spanish conquest, the days were counted from 1, so that the Haab’ year began with the date 1 Pop (instead of 0 Pop) for some time.

In principle, the last day of a Haab’ month is not numbered 19 (or 20), but is labelled as the day before the next month with the glyph of the following month and the addition seated

. 19 Pop was therefore written as seated Wo’

.

Im Gegensatz zum rituellen Tzolk’in wurden die Tageszahlen 0 bis 19 eines Haab’-Monats täglich hochgezählt, nach dem 19. eines Monats folgte der nullte des nächsten Monats, nach dem 18. Monat folgten die fünf Unglückstage des Kurzmonats Wayeb’. Der erste Tag der Schöpfung fiel auf 8 Kumk’u, den achten Tag des Monats Kumk’u. Die Kombination 4 Ajaw mit 8 Kumk’u ist nach 52 Haab’-Jahren erreicht und wird Kalenderrunde

genannt. Sie entspricht 73 Tzolk’in-Perioden und exakt 130 synodischen Venusumläufen.

Der Haab’ Kalender wurde mit der Eroberung durch die Spanier verändert, die Tage wurden ab 1 gezählt, sodass für einige Zeit das Haab’-Jahr mit dem Datum 1 Pop (statt 0 Pop) begann.

Grundsätzlich wird der letzte Tag eines Haab’ Monats nicht mit 19 (bzw. 20) nummeriert, sondern als Vortag des kommenden Monats mit der Glyphe des Folgemonats und dem Zusatz seated

gekennzeichnet. 19 Pop wurde also als seated Wo’

geschrieben.

Sources, links and further readingQuellen, Links und weiterführende Literatur

ReferencesReferenzen

The background picture shows the silhouette of the classical Maya territory.

The characters of the font which I have put together by myself are based on the preserved stelae inscriptions.

The picture for the explanation of the characters for Balam is taken from the book Breaking the Maya Code

by Michael D. Coe, Thames and Hudson Ltd., London, 1992.

For the calculation of the Mayan calendar date, I used the generally accepted GMT+2 correlation, which sets the zero date to 13 August 3114 BCE or JDN 584285.

Das Hintergrundbild zeigt die Silhouette des klassischen Maya-Territoriums.

Die Schriftzeichen der Schrift, die ich selbst zusammengestellt habe, basieren auf den erhaltenen Steleninschriften.

Das Bild zur Erklärung der Schriftzeichen für Balam stammt aus dem Buch Breaking the Maya Code

von Michael D. Coe, Thames and Hudson Ltd., London, 1992.

Für die Berechnung des Maya-Kalenderdatums habe ich die allgemein anerkannte GMT+2-Korrelation verwendet, die das Nulldatum auf den 13. August 3114 v.d.Z. oder JDN 584285 festlegt.